“Among summits, I am Meru…among standing things, Himalaya.” (Bhagavad-Gitā, 10.23, 25)

In one of the most revered Hindu texts, dating back at least two millennia—the Bhagavad-Gītā or “Song of the Blessed Lord”—the divine incarnation Krishna gradually reveals his identity to his friend and disciple, the warrior-prince Arjuna: a revelation that culminates in a cosmic vision in the text’s eleventh chapter. But just before that, there is a verbal epiphany in which the God-man offers a series of similes for his transcendent being. Notably, two of them reference mountains in that mighty chain of peaks, containing all of earth’s highest points, that comprise the northern boundary of the Indian subcontinent. Indeed, the “abode of snow” (Himālaya) has been revered by South Asians throughout recorded history as the “land of the gods” (deva-bhūmi), and among its many dazzling white summits, several, including Kailash, Meru, and Nanda Devi have been singled out for special veneration as embodied deities in their own right, and as the goals of pilgrims and seekers from all the spiritual traditions indigenous to the region: Buddhism, Hinduism, Jainism, and Sikhism.

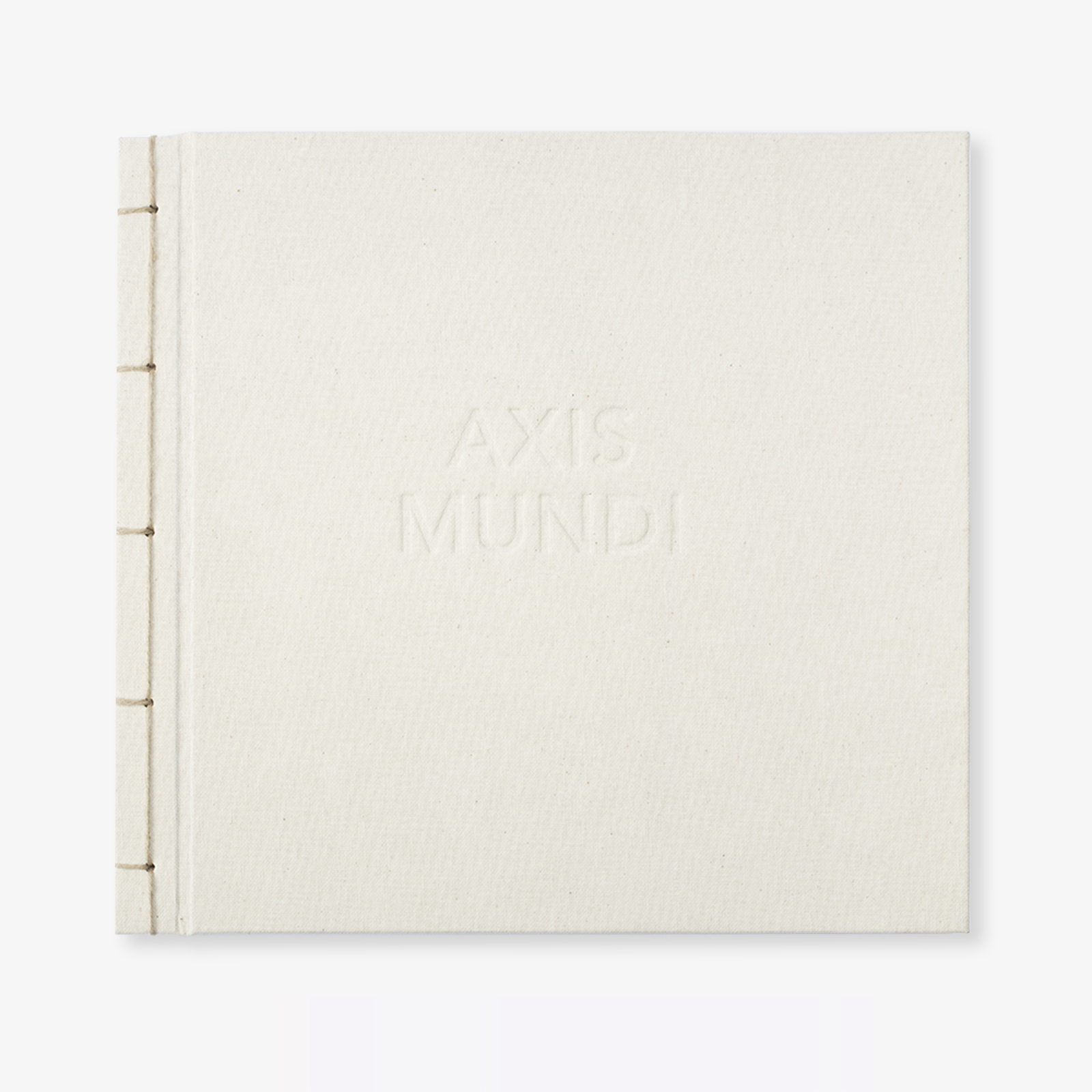

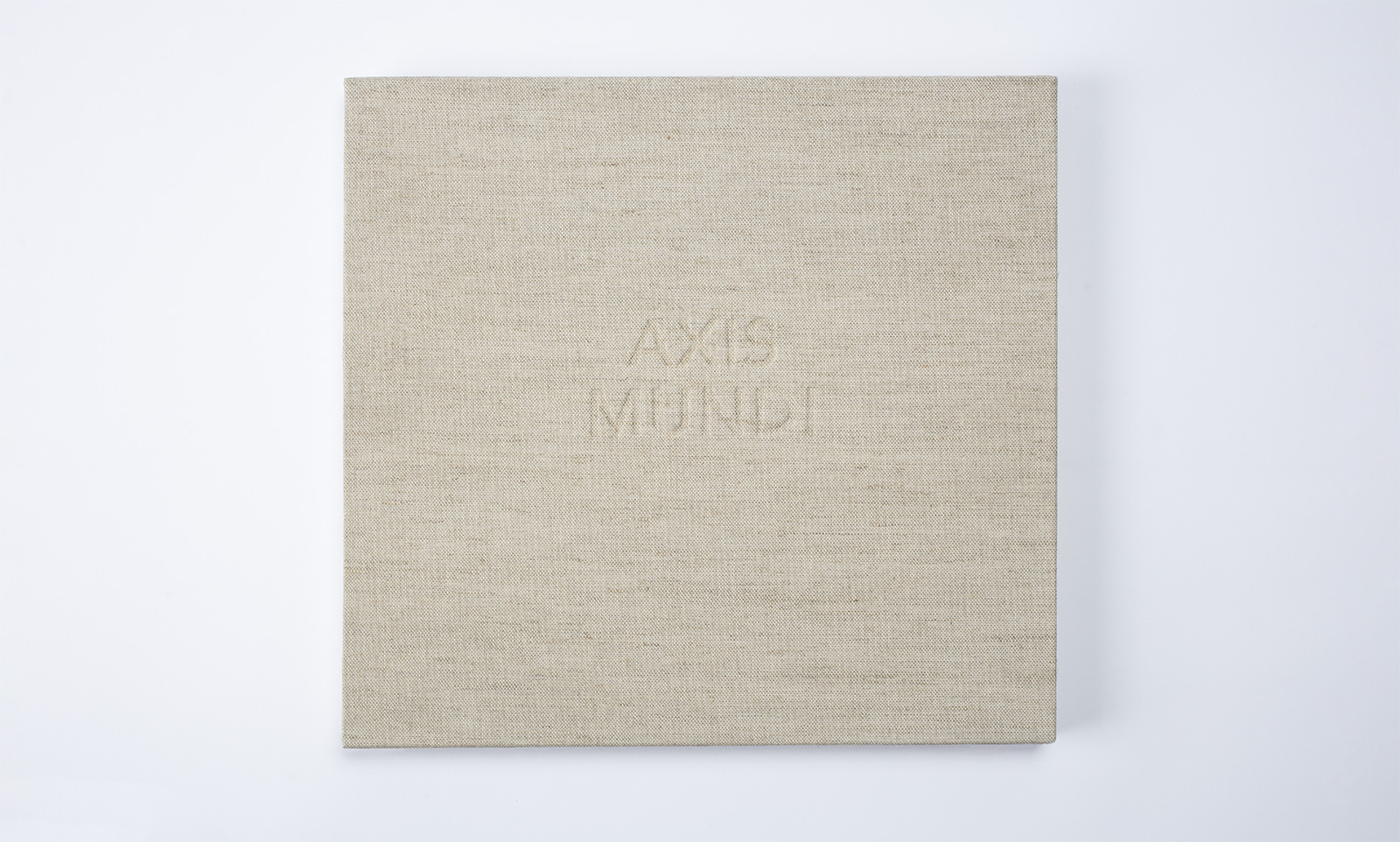

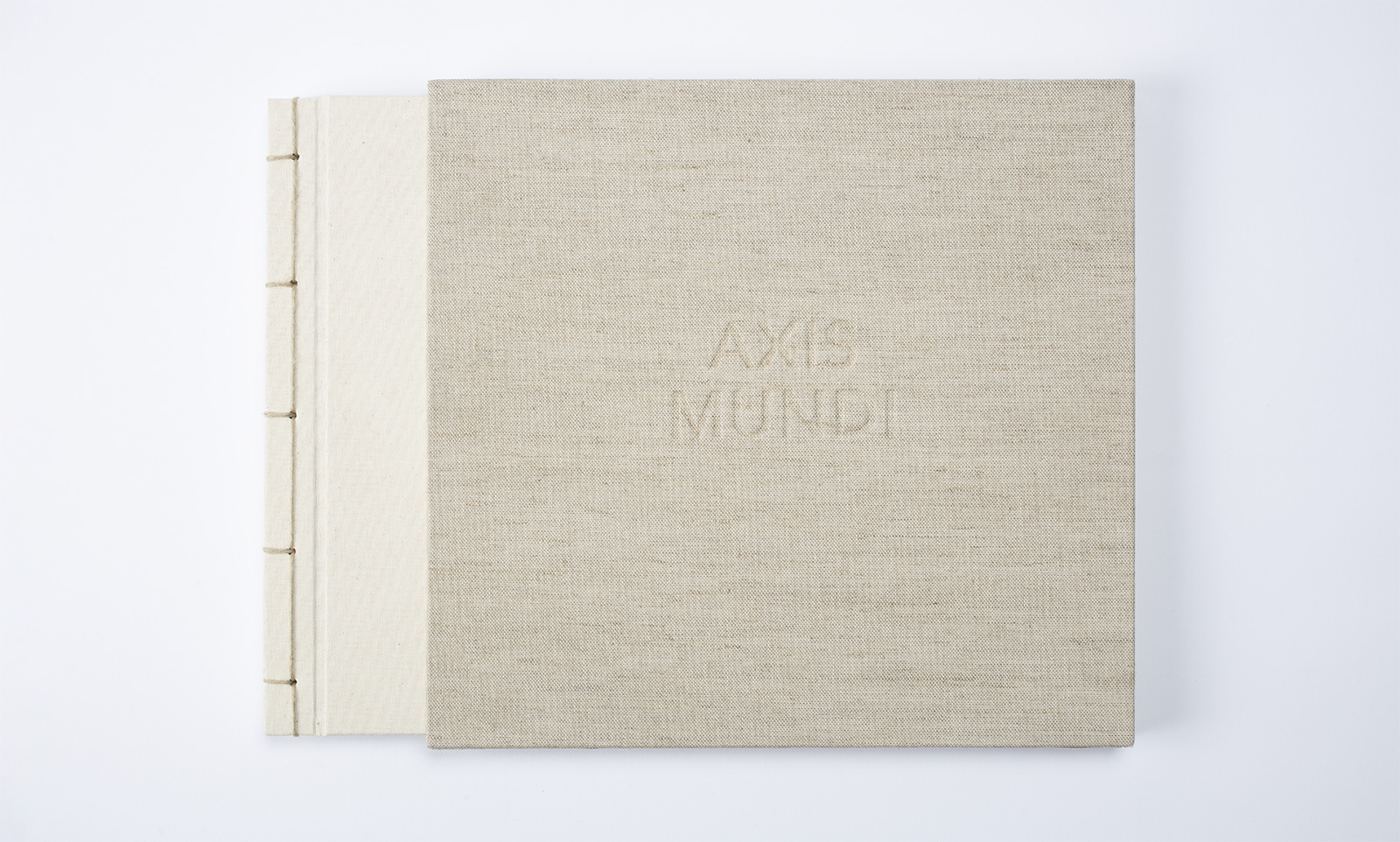

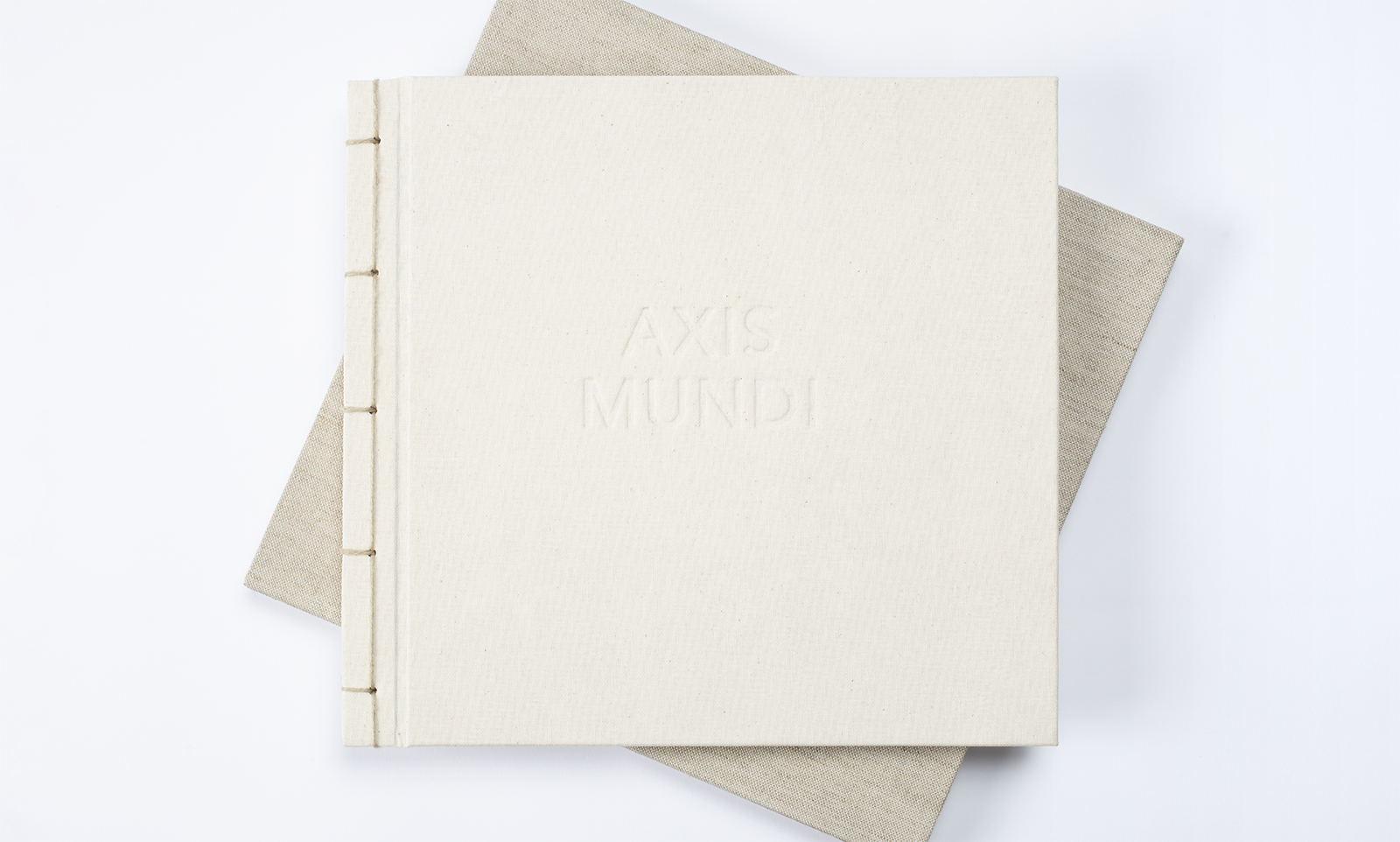

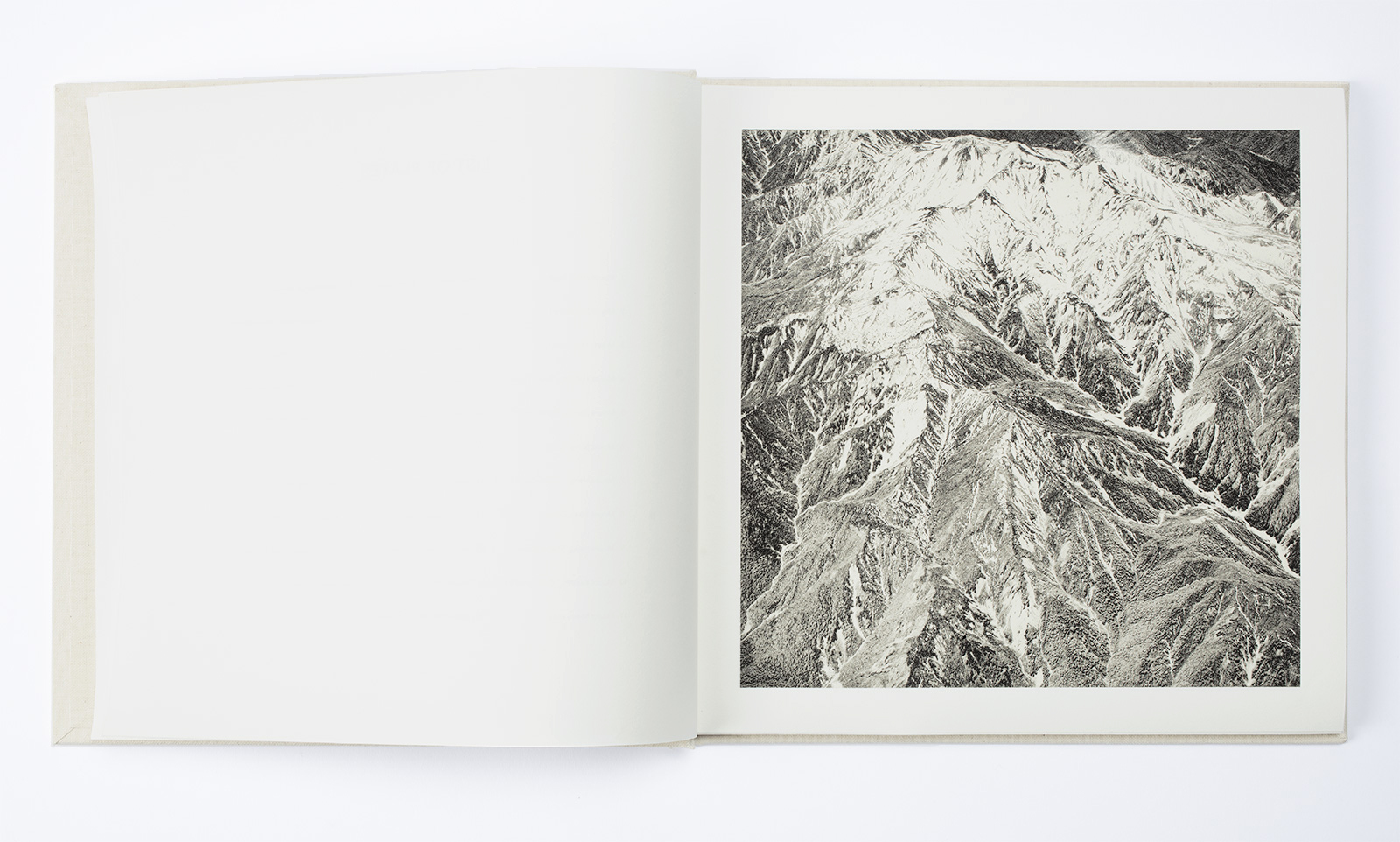

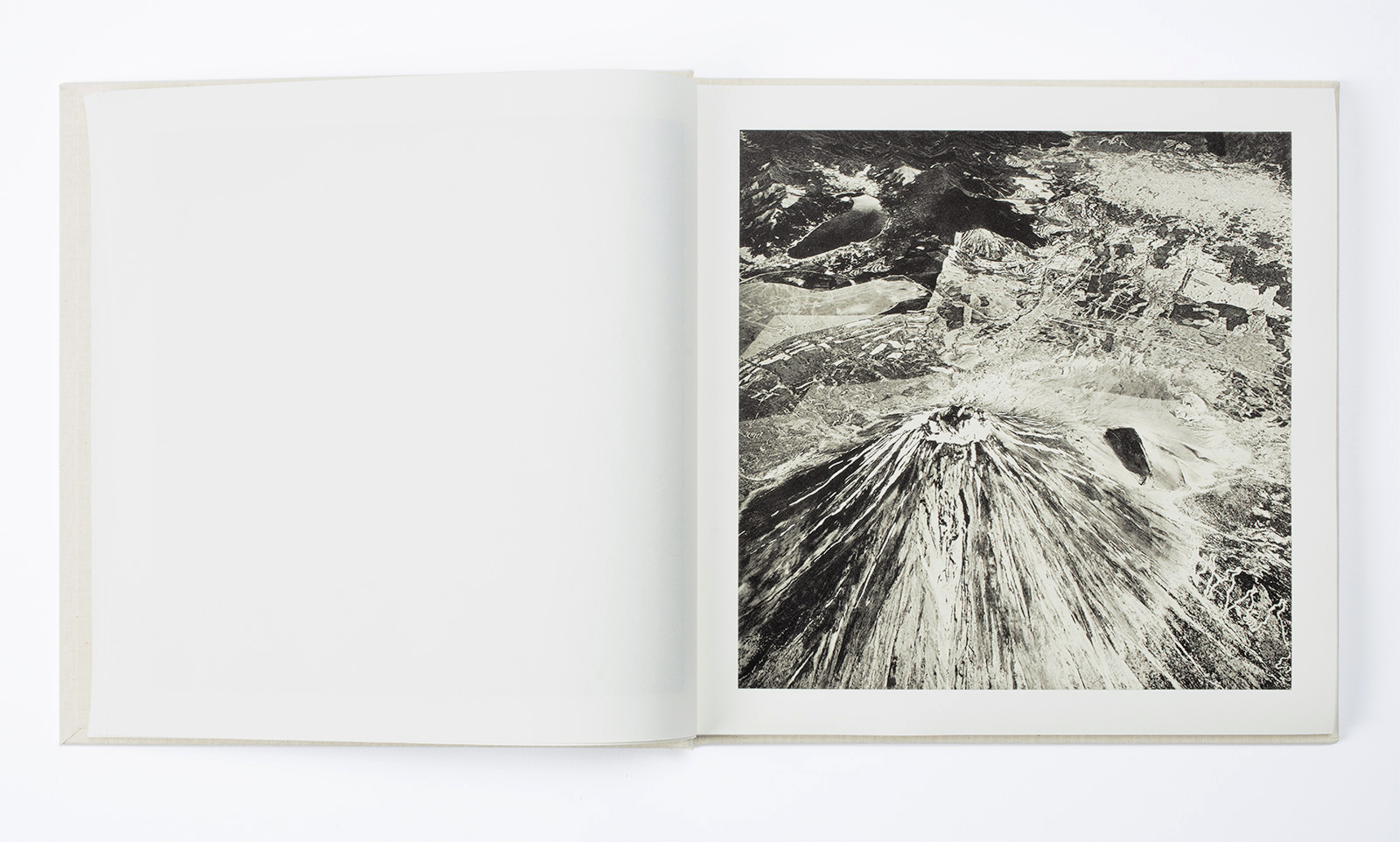

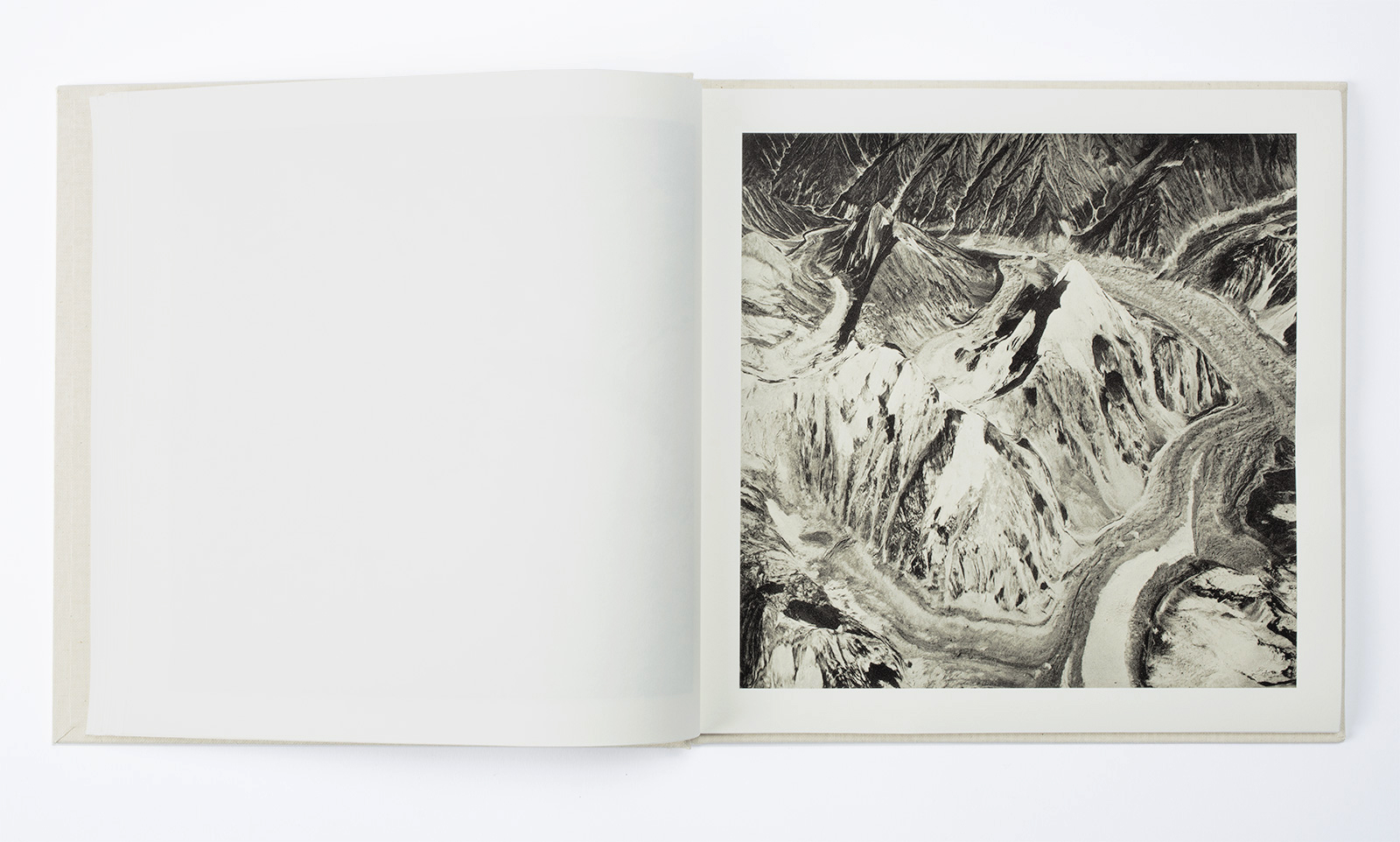

Such admiration for mountains as inspiring emblems of both transcendence and permanence is of course widely shared among human cultures. In the recent work of artist and printmaker Beth Ganz, the theme of the sacred mountain as world-axis is celebrated once again through a unique synthesis of contemporary and 19th century technologies: satellite photography, digital transfer, and the laborious process of copper plate photogravure engraving, creatively manipulated to yield original evocations

of lofty summits, many of which have been revered for centuries or even millennia. The present series features sacred mountains of one longitudinal hemisphere of our globe, encompassing Eurasia, Africa, and the Pacific: Damavand (plate 16), Meru (plate 11), Olympus (plate 20), Sinai (plate 21), Kilimanjaro (plate 22), Kailash (plate 10), and twenty-seven others appear in striking perspectives, deep contrasts, and runic patterns that invite contemplation. Like Hokusai’s “Thirty-six Views of Mt. Fuji” (another peak featured here; plate 2), but on a global scale, Ganz’s thirty-two works explore and evoke the awe, grandeur, and enduring sacrality of some of the earth’s most revered natural features.

PHILIP LUTGENDORF

Professor of Hindi and Modern Indian Cultures, Emeritus; University of Iowa